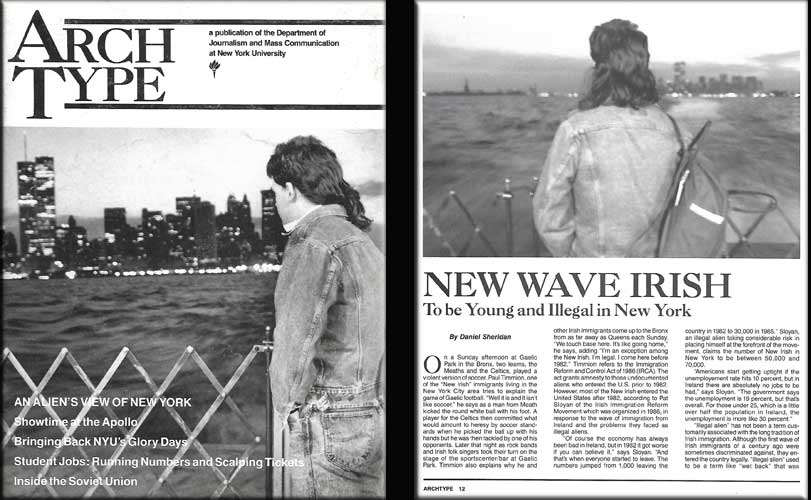

New Wave Irish: To Be Young and Illegal in New York

Article and photos by Daniel A. Sheridan

This article appeared in Arch Type, the New York University Journalism School Magazine — Fall, 1988.

On a Sunday afternoon at Gaelic Park in the Bronx, two teams, the Meaths and the Celtics, played a violent version of soccer. Paul Timmion, one of the "New Irish" immigrants living in the New York City Area tries to explain the game of Gaelic Football. "Well, it is and it isn't like soccer," he says as a man from Meath kicked the round white ball with his foot. A player for the Celtics then committed what would amount to heresy by soccer standards when he picked the ball up with his hands but was then tackled by one of his opponents.

Later that night as rock bands and Irish folk singers took their turn on the stage of the sportscenter/bar at Gaelic Park, Timmion explains why he and other Irish immigrants come up to the Bronx from as far away as Queens each Sunday. "We touch base here. It's like going home,"he says adding, "I'm an exception among the New Irish. I'm legal. I came here before 1982."

Timmion refers to the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA). The act grants amnesty to those undocumented aliens who entered the U.S. prior to 1982. However, most of the New Irish entered the United States after 1982, according to Pat Sloyan of the Irish Immigration Reform Movement which was organized in 1986 in response to the wave of immigration from Ireland and the problems they faced as illegal aliens.

"Of course the economy has always been bad in Ireland, but in 1982 it got worse if you can believe it," says Sloyan. "And that's when everyone started to leave. The numbers jumped from 1,000 leaving the country in 1982 to 30,000 in 1985." Sloyan, an illegal alien taking considerable risk in placing himself at the forefront of the movement, claims the number of New Irish in New York to be between 50,000 and 70,000.

"Americans start getting uptight if the unemployment rate hits 10 percent, but in Ireland there are absolutely no jobs to be had," says Sloyan. "The government says the unemployment is 19 percent, but that's overall. For those under 25, which is a little over half the population in Ireland, the unemployment is more like 30 percent."

"Illegal Alien" has not been a term customarily associated with the long tradition of Irish immigration. Although the first wave of Irish immigrants were sometimes discriminated against, they entered the country legally. "Illegal Alien" used to be a term like 'wet back' that was reserved for Mexicans trying to avoid the Border Patrol along the Rio Grande. While the Irish may get off the plane with their backs fairly dry, still the vast majority of them are illegal aliens. With their illegal status, the New Irish are trying to make Americans, particularly Irish-Americans, aware that there is more to being an illegal alien than stealing American jobs and not paying taxes.

Illegal aliens are not eligible for health insurance which many New Irish find as a complete shock coming from a country with socialized medicine. Illegal aliens cannot open bank accounts or be considered for financial aid for college, and only American citizens can join the armed forces or vote in general elections. Also, as a result of the so-called employer sanction law, illegal aliens are greatly restricted among the jobs open to them. Most jobs require an I-9 form which verifies employment eligibility and identity. Because jobs involving domestic housework don't require the I-9 form, many young Irish girls find work here as nannies, which seems to have coincided with the increase in working mothers.

Recently, one Irish nanny who asked that her last name not be used, Bernie (short for Bernadette) held a baby in her right arm as she directed two four-year-old toddlers underneath a subway turnstile. Her sister Susan, who arrived from Ireland two months ago, carried the stroller and a yellow wiffle baseball bat. "Here J.D. would you mind taking the basebat," she says, pausing and then correcting herself, "or whatever you call this thing."

In Central Park, Bernie sat on some rocks and watched the two children in the playground below, while Susan held the baby in her arms. "It's very rare that you would find a whole family moving to America; it's mainly just the young Irish who are leaving. Usually as soon as they finish secondary school," says Bernie who came to the United States two years ago when she was 18. Although her family lives in County Mayo on the west coast of Ireland, her father could only find work in Dublin, six hours away by train on the other side of the country.

In Central Park, Bernie sat on some rocks and watched the two children in the playground below, while Susan held the baby in her arms. "It's very rare that you would find a whole family moving to America; it's mainly just the young Irish who are leaving. Usually as soon as they finish secondary school," says Bernie who came to the United States two years ago when she was 18. Although her family lives in County Mayo on the west coast of Ireland, her father could only find work in Dublin, six hours away by train on the other side of the country.

"He could only come home on the weekends," said Bernie. Another sister, Roseline, wants to come over as soon as she finishes school. Bernie had gotten another sister, Susan, a job as a nanny before she emigrated.

"There's no incentive to work in Ireland, the wages are so poor," says Bernie, who explained that collecting the 'dole' (welfare) would amount to 35 pounds ($60) weekly. "If you work hard and come home with a week's wage of 40 pound, what's the point if you can do just as well on the dole?"

What troubled Bernie most about being illegal is "I can't go back home to visit." Presently, she is being sponsored by the family she's working for and leaving the United States would invalidate her sponsorship. "I couldn't risk going through customs," she says.

Like many of the New Irish, Bernie and her sister Susan could not qualify for legal residence in the U.S. (commonly known as 'green cards') when they decided to leave Ireland. In 1986, only 730 green cards were allotted for Irish immigrants according to Sean Minihane, cofounder of the Irish Immigration Reform Movement.

The Irish Immigration Reform Movement played a significant role in getting the Kennedy/Simpson Immigration Bill drafted. The bill, which establishes a point system giving those with English language skills 20 points, promises to allow as many as 8,400 Irish people into the U.S. each year.

Although the Kennedy/Simpson Bill would not grant amnesty to those illegal aliens already here, a bill sponsored by Senator Al D'Amato and Congressman Joe Dioguardi would provide a means for illegal aliens to qualify for citizenship. Two years after a three-year stint in the armed forces, veterans would become eligible for a 'green card.' "Sure I'd join," says Chris an 18 year-old illegal Irish immigrant who asked that his last name not be used. "Three years of your life isn't much to ask for a green card," he adds.

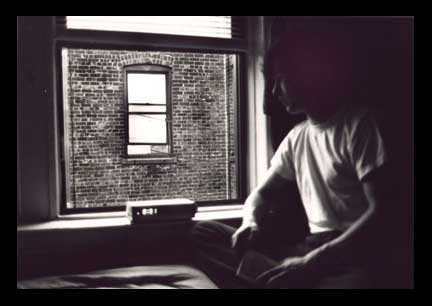

Chris walked into the kitchen of his apartment near Gun Hill Road in the Bronx and shouts to his 20 year-old brother. "How does chili sound, Steve?" Steve said that it sounded all right to him as he reads an Irish newspaper in the livingroom. "This is the paper form my hometown. The guy down the corner charges three times what it's worth," he says. When he finished secondary school Steve considered going to college. "Graduation is different in Ireland. In America, they buy their kids cars, but what we got were immigration seminars where they would tell us what our rights were abroad," Steve says sarcastically.

Three years ago, Chris and Steve went to London to work so they could earn enough for airfare to the U.S. After eight months in London, they purchased plane tickets and arrived in the United States on March 13th, 1985. "The main thing was seeing the St. Patrick's Day Parade: the largest parade in the world and it's for the Irish," Chris said in disbelief as he serves the chili.

Steve, an illegal Irish immigrant, looks out his Bronx apartment. Photo by Daniel A. Sheridan

On the plate was what looked like Irish Stew. There were chunks of beef, potatoes, and carrots in brown gravy. "So how's the chili?" Chris asks. There were a couple of kidney beans and chili powder had been sprinkled on the potatoes. "It's good chili," his brother affirms.

In between mouthfuls of buttered bread and Irish chili, Chris and Steve describe what it was like coming to America. When they arrived in Newark Airport, they had only $200 apiece and a duffle bag of clothes. Their uncle drove them through mid-town Manhattan. "It was like being inside a TV. We just walked around like this," Steve says tilting his head backwards.

When they got situated with jobs, they moved into an apartment with 11 other immigrants. "It wasn't as bad as it sounds, we had some great times," says Steve who started out as a window-washer and then became a security guard. "Imagine me, an 'illegal' being a security officer," he says. They eventually were able to get jobs as construction workers, making $20 an hour.

They enjoy a new electronic life: "Steve has a phone in his room and I have one in mine, but in Ireland we never had a phone," says Chris, who also has an answering machine hooked up. In the living room are a color television and a VCR. "You were lucky if you had a bike in Ireland," says Chris who now owns a car as well as his brother.

"Don't get me wrong," explains Chris. "I loved Ireland an awful lot but there's no future there. After we left, my Dad could no longer put bread on the table and had to move the family to London. Things used to be good, but then everything went downhill."

Chris points to pictures he had taken of wild Irish horses roaming the countryside in County Mayo. He shows another photo, saying, "You see that island. Me and Steve took a boat out there and camped the night." Chris has not seen his family in three years. "I'm sure amnesty will come some day. I'm prepared to wait," he says.

This article appeared in Arch Type, the New York University Journalism School Magazine — Fall, 1988.