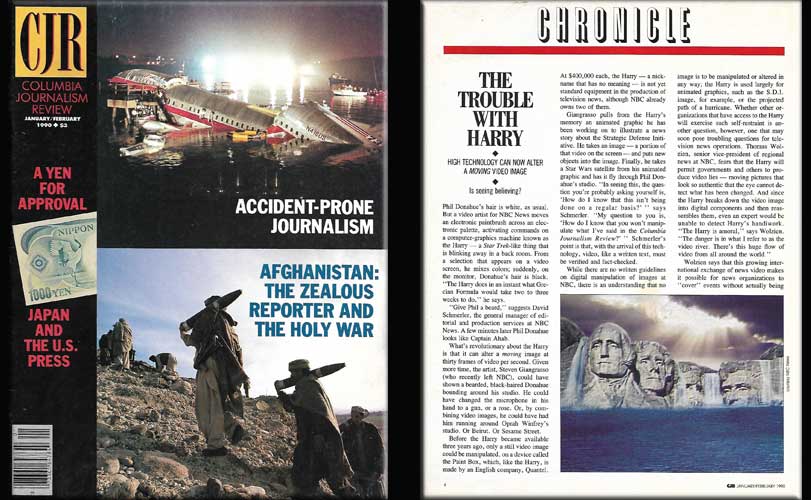

The Trouble with Harry: Is Seeing Believing?

Article by Daniel A. Sheridan

This article appeared in the Columbia Journalism Review — Jan/Feb 1990.

Phil Donahue's hair is white, as usual. But a video artist for NBC News moves an electronic paintbrush across an electronic palette, activating commands on a computer-graphics machine known as the Harry - a Star Trek-like thing that is blinking away in a back room. From a selection that appears on a video screen, he mixes colors; suddenly, on the monitor, Donahue's hair is black. "The Harry does in an instant what Grecian Formula would take two to three weeks to do," he says.

"Give Phil a beard," suggests David Schmerler, the general manager of editorial and production services at NBC News. A few minutes later Phil Donahue looks like Captain Ahab.

What's revolutionary about the Harry is that it can alter a moving image at thirty frames of video per second. Given more time, the artist, Steven Giangrasso (who recently left NBC), could have shown a bearded, black - haired Donahue bounding around his studio. He could have changed the microphone in his hand to a gun, or a rose. Or, by combining video images, he could have had him running around Oprah Winfrey's studio. Or Beirut. Or Sesame Street.

Before the Harry became available three years ago, only a still image could be manipulated, on a device called the Paint Box, which like the Harry, is made by an English company, Quantel. At $400,000 each, the Harry - a nickname that has no meaning - is not yet standard equipment in the production of television news, although NBC already owns two of them.

Giangrasso pulls from the Harry's memory an animated graphic he has been working on to illustrate a news story about the Strategic Defense Initiative. He takes an image - a portion of that video on the screen - and puts new objects into the image. Finally, he takes a Star Wars satellite from his animated graphic and has it fly through Phil Donahue's studio. " In seeing this the question you're probably asking yourself is 'How do I know that this isn't being done on a regular basis?' " says Schmerler. "My question to you is, 'How do I know that you won't manipulate what I've said in the Columbia Journalism Review?' " Scmerler's point is that, with the arrival of this technology, video, like a written text, must be verified and fact-checked.

While there are no written guidelines on digital manipulation of images at NBC, there is an understanding that no image is to be manipulated or altered in any way; the Harry is used largely for animated graphics, such as the S.D.I. image, for example, or the projected path of a hurricane. Whether other organizations that have access to the Harry will exercise such self-restraint is another question, however, one that may soon pose troubling questions for television news operations. Thomas Wolzien, senior vice-president of regional news at NBC, fears that the Harry will permit governments and others to produce video lies - moving pictures that look so authentic that the eye cannot detect what has been changed. And since the Harry breaks down the video image into digital components and the reassembles them, even an expert would be unable to detect Harry's handiwork. "The Harry is amoral," says Wolzien. "The danger is in what I refer to as the video river. There's this huge flow of video from all around the world."

Wolzien says that this growing international exchange of news video makes it possible for news organizations to "cover" events without actually being on the scene - by using somebody else's video - and that television economics encourages this trend. The sources of this "video river" range from state-run broadcasting organizations to stringers, and it can be very difficult to determine where a video image has come from - let alone whether it has been altered.

As one hypothetical example, Wolzien imagines a videotape of Nicaraguan PT boats attacking a U.S. destroyer. The boats look as if they are shooting; the administration says the tape is real; the guns certainly flash? Do we go to war? Or is it the Harry?

Wolzien argues that television news organizations must identify sources of their video images, the way responsible journalists identify sources in stories. And NBC, he says, is working on a sort of universal product code that would tell a news organization who shot a video and where, and who handled it afterwards. To safeguard the video river, of course, such coding would have to be agreed upon and used worldwide.

Earlier developments in digital technology raised similar credibility issues for still photographers and editors. Seven years ago, using a machine called the Scitex, National Geographic, for example, was able to move an Egyptian pyramid on one of its covers. "We did move it slightly," says Jim Whitney, associate director of engraving and printing at National Geographic, "but we don't do that anymore."

Scitex technology was also used on the cover of a book of U.S. photographs, A Day in the Life of America, published in 1986; the picture - a scene of a moon, a cowboy on a horse, and a tree - is a digital composite. "That is not a photograph; it's not a truthful representation of what happened," says Ed Hart, a picture editor at UPI.

Scitex has proved valuable as a production tool, and as an electronic airbrush for advertisers and others, but its potential for making undetectably false pictures is worrisome. "Don't get me wrong - I sleep nights. But our credibility is at stake," Hart says. Now that the Harry has arrived, television journalists, too, have to guard against pictures that lie.

This article appeared in the Columbia Journalism Review — Jan/Feb 1990.